In an age where even the mysteries of black holes 6000 light years away has been explored as if they were right alongside us, would you believe us if we said that scientists still don’t know quite a bit about how the Indian Ocean works? Without many samples, researchers are frequently left in the dark about the ways that fish, plankton and other aquatic life flourishes in the area.

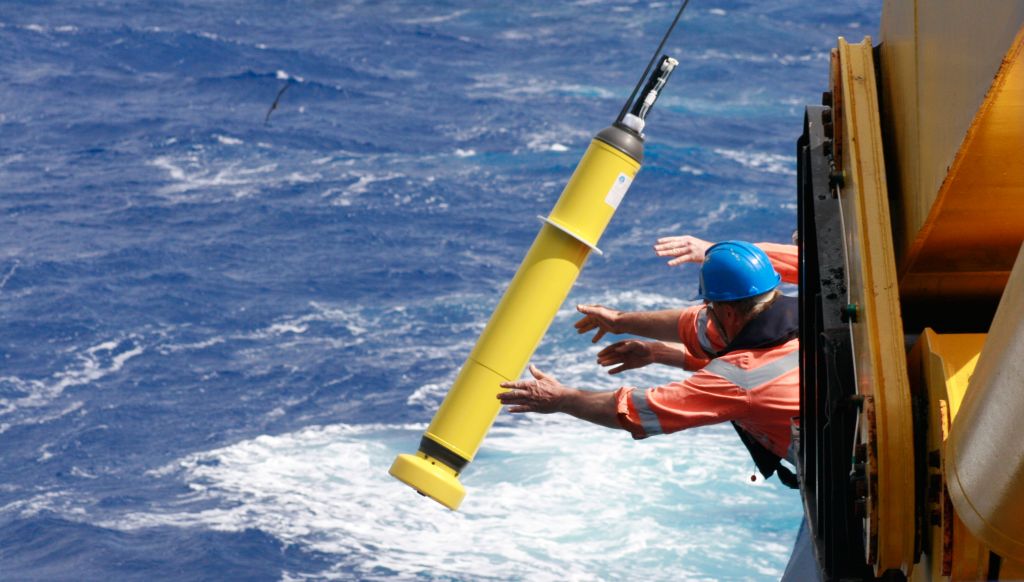

This could soon change, though. The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia’s national science agency, has teamed with their Indian counterparts at the Indian National Institute of Oceanography to release bio robots into the Indian Ocean in order to “revolutionise” our knowledge of a marine environment upon which hundreds of millions of people rely. These robots will measure both the biological and physical traits of the ocean to learn what makes it healthy. Much like the Argo machines studying Arctic waters, they’ll float deep underwater (at around 6,600 feet) and drift with the current. They’ll usually need to surface only when they’re transmitting their findings. Combined with satellite imagery, the BioArgo drones should give researchers a true “3-dimensional picture” of the Indian Ocean.

Key questions the scientists will be examining include how the eddies that spin off the WA coast into the interior of the Indian Ocean transport that coastal water and how that feeds the production in the interior, said CSIRO’s Dr Nick Hardman-Mountford.

“We know they can go as far as Madagascar but we don’t know how long that lasts for. Also in the northern Indian Ocean … in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal they have low oxygen waters, and they seem to be increasing in the Bay of Bengal.”

As well as questions around climate change, there are also food, energy and health security issues that need investigation. “The Indian Ocean rim countries make up one sixth of the world’s population. A lot of people rely on it,” said Hardman-Mountford. “About half the world fishers live in the eastern Indian Ocean, catching about 7m tonnes of fish per year. It’s the third-largest tuna fishery in the world with an estimated value of $2-3bn a year. It’s a really economically important region.

The $1m bio Argo floats project is funded for three years, in part by the Australian government under the Australia-India Strategic Research Fund.